Konstantin Stanislavski’s An Actor Prepares (1936) is more than required reading for acting majors; it is the crucible in which most contemporary performance theory was forged. The book’s fictional diary format—tracking the progress of the anxious first-year student Kostya under the fierce but caring eye of the master-teacher Tortsov—lets us witness technique being discovered, resisted, broken, and finally absorbed. Almost ninety years later, the material still feels startlingly current because it dramatizes the process rather than prescribing cold formulas.

Yet many modern actors skim the text looking for quick hacks and miss its rich, incremental structure. This article doubles down on detail, unpacking each chapter’s core principles, showing why they matter, how to practise them, and where they connect to newer methods. The goal is a practical roadmap—something you can print, annotate, and carry into rehearsal tonight.

1 The Book’s Story-Telling Format—Why It Still Works

Stanislavski could have written a standard textbook, but he chose a novel-length narrative so that technique would land viscerally. The story creates empathy: when Kostya forgets his line because he’s frozen by self-consciousness, we cringe because we have all been there. Tortsov’s corrections, delivered in vivid scenes instead of lecture notes, show technique in motion.

This structure also builds progressive layering. Early chapters centre on relaxation; later chapters revisit the same exercise under increasing dramatic pressure. Readers experience the spiral syllabus firsthand, learning that mastery is not linear but cyclical.

Three built-in advantages of the diary format

| Advantage | How It Helps Actors Today |

|---|---|

| Relatability | Kostya’s self-doubt mirrors our own rehearsal frustrations, reducing isolation. |

| Demonstration | Classroom episodes serve as concrete case studies, easier to apply than abstract theory. |

| Cumulative logic | Each entry introduces one new element while revisiting earlier ones, modelling healthy rehearsal habits. |

Take-away Keep a rehearsal journal. Mirror Kostya’s habit of logging tension spikes, objective notes, and post-run reflections. Review weekly to track growth and recurring blocks.

2 Relaxation: The Zero-Point of Creative Readiness

Stanislavski opens by identifying excess muscular tension as the great enemy of truthful acting. Tension constricts breath, vocal resonance, and blood flow, pushing the actor into mechanical “indicating.” The antidote is conscious relaxation, sometimes nicknamed the state of cat-like readiness: loose yet alive.

Contemporary neuroscience backs him up. Chronic sympathetic-nervous activation (the “fight-or-flight” state) hijacks the prefrontal cortex, crippling impulse control and creative association. Systematic relaxation drops the body into parasympathetic dominance, restoring fine-motor control and imaginative flexibility.

Stanislavski’s basic relaxation sequence

- Progressive scan from forehead to feet, releasing micro-contractions.

- Diaphragmatic breathing—inhale 4 counts, suspend 2, exhale 6.

- Neutral alignment—pelvis untucked, sternum buoyant, knees soft.

- Dynamic shake-out—free swing of arms and legs to dissolve residual tension.

Extended drill After scanning, stand and deliver a section of text. Note tiny posture shifts or vocal drops. Repeat the scan, then re-deliver. Compare recordings to quantify improvement.

3 Concentration & the Circles of Attention

To act well is to focus with surgical precision while surrounded by distractions. Stanislavski visualises attention as three elastic circles of expanding size. Actors begin in the small circle—objects within arm’s reach—before widening to the medium (entire room) and large (whole auditorium).

Modern sport psychologists call the same skill “attentional bandwidth.” Training narrow-to-broad focus conditions the brain to filter noise in live performance without deadening peripheral awareness—a must for camera work, where a boom mic might hover inches away.

Three Circles at a Glance

| Circle | Practical Example | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| Small | Inspecting a teacup’s rim for chips | Staring blankly, losing animation |

| Medium | Noticing partner’s footwear and body weight | Over-monitoring audience reactions |

| Large | Feeling the energy of the back row without breaking fourth wall | Spreading gaze too wide, appearing unfocused |

Solo exercise Place three objects at 1 ft, 6 ft, and 20 ft. Shift attention in 10-second bursts: first the coin in your palm, then the chair across the room, then the exit sign. Add text as you change circles, maintaining vocal ease.

4 Given Circumstances: Research as Creative Fuel

Stanislavski coined “given circumstances” to mean every factual detail—time, place, social climate, weather, and prior action—that frames the scene. Without them, objective work floats unmoored; with them, it gains irresistible logic.

Today, actors benefit from digital archives, dialect databases, and even climate simulators. But research must stay selective: gather enough to spark imagination, not enough to bury it under trivia. Aim for sensory triggers—sounds, fabrics, smells—that can be played onstage.

Research Checklist

- Historical timeline (major political or cultural events that shape worldview)

- Geography & climate (altitude changes breathing; humidity alters costumes)

- Economics & diet (poor characters move differently than well-fed ones)

- Immediate past (what happened 60 seconds before your entrance?)

- Social hierarchies (rank alters eye contact and physical distance)

Pro tip Translate each researched fact into a playable adjustment: “drafty attic” → hunch shoulders, rub arms; “aristocrat” → slower head turns, softer footsteps.

5 The “Magic If”: Switching on Imagination

Where facts end, imagination begins. By asking “If I were in these circumstances, how would I behave?” the actor invites authentic response rather than forced mimicry. The Magic If is like VR goggles for the mind, overlaying new rules on familiar space.

Cognitive science labels this counterfactual simulation, a process known to activate mirror-neuron networks and foster empathy. Repeated use wires the brain to treat fictional stakes as subjectively real, raising spontaneity and risk-taking.

Applications of the Magic If

- Props: If this blank paper carried my exile order…

- Space: If this rehearsal room were a damp prison cell…

- Relationship: If my scene partner were my estranged twin…

Pair drill Exchange mundane objects (a pen, a water bottle). Verbally reinvent them via Magic If for 60 seconds, then improvise dialogue while sustaining the new circumstance.

6 Objectives, Obstacles & Actions — The Engine of Drama

Stanislavski reframed acting as psychology in action. Every character pursues an objective—something urgent and specific. That pursuit meets obstacles (external blocks, internal fears, social codes) and sparks a succession of actions (playable verbs) aimed at overcoming resistance.

Breaking text this way replaces vague “playing emotion” with testable strategy. Audiences may not articulate objectives, but they feel the electricity generated when a tactic either lands or fails.

Hierarchy of Wants

| Level | Definition | Example from Romeo & Juliet |

|---|---|---|

| Super-objective | Play-long driving goal | Romeo: “Secure lasting love” |

| Scene objective | Want for that scene | “Marry Juliet in secret” |

| Beat objective | Micro-aim inside a scene | “Persuade Friar Lawrence” |

Sample Playable Verbs

| To Charm | To Threaten | To Plead | To Seduce | To Mock |

Script-markup drill Underline every objective in blue, obstacles in red, tactics in green. Speak each beat while glancing at colour cues to internalise shifts subconsciously.

7 Units & Beats: Carving the Script for Precision

Tortsov teaches Kostya to slice scenes into units (a.k.a. beats) so that shifts in objective pop like chord changes in music. Without beats, performances flatten into one-note sincerity; with them, they gain shape and suspense.

Modern directing often begins with a “beat map” projected in the rehearsal room. Actors annotate it collaboratively, ensuring everyone’s unit breaks align, preventing partner-blocking or tempo clashes.

Three-Step Beat-Finding Method

- Cold read for narrative flow—no stopping.

- Analytical read—pause when the character’s want or tactic changes; mark

//. - Label—in the margin, write the new verb and predicted emotional tempo.

Advanced tip Assign each beat a percussive sound (click, clap) and rehearse with a stage manager marking real-time transitions to burn the architecture into muscle memory.

8 Emotion Memory: Myths, Realities & Safe Practice

Emotion memory—re-sensitising past experiences to kindle present feelings—has sparked confusion and abuse. Stanislavski never endorsed self-harm for “authenticity.” He advocated sensory fragments (smell of lilacs, crunch of snow) to gently awaken visceral states, always under conscious control.

Contemporary trauma science warns that diving into unprocessed memories can retraumatise. Ethical pedagogy therefore emphasises analogous, not identical memories and builds grounding exits (breathing, neutral imagery) before exploration.

Guidelines for Responsible Use

- Focus on senses Recall tactile, olfactory, or auditory details, not narrative trauma.

- Keep a safety exit Agree on a neutral cue (e.g., count backwards) to reset.

- Analogous substitutions Choose experiences with similar emotional temperature but lower personal risk.

Rehearsal protocol Work in pairs with a designated witness. After exercise, share physical sensations, then debrief on distance kept between personal life and character life.

9 Tempo-Rhythm: The Musicality of Human Behaviour

Life pulses in variable tempo and rhythm. A grieving parent may move in slow motion yet think in lightning-fast spirals. Stanislavski urges actors to locate both inner tempo (thought speed) and outer rhythm (body pace), then manipulate contrast for dramatic irony.

Modern neuroscientists describe brain-state changes in terms of oscillatory frequency. Matching inner-outer tempo sets up neural coherence; mismatching them can signal dissonance or deceit—powerful storytelling tools.

Tempo-Rhythm Drill

- Read a monologue at 200 % speed—note tension points.

- Read at 50 % speed—note sagging moments.

- Choose a hybrid tempo that reveals objectives and masks private agenda.

Partner extension Overlay opposing rhythms: one actor fast inside/slow outside, the other slow inside/fast outside. Observe friction in the space between.

10 Communion & “Public Solitude”

Stanislavski distinguishes communion (true connection) from mere eye contact. It is a full-body listening state—ears, skin, intuition—all absorbing and answering partner stimulus. When communion is absent, lines sound recited; when present, even silence crackles.

The paradox of theatre is that actors must achieve private authenticity in public view—what Stanislavski calls public solitude. Training communion keeps attention bouncing between partner and objective, so audience observation fades into background hum.

Non-verbal game Stand in pairs, 4 ft apart. Mime throwing an invisible object whose weight, temperature, and resistance change on each toss. Add text without dropping the sensory ball. Film and review: if the object vanishes, communion slipped.

11 The Method of Physical Actions—Stanislavski’s Later Pivot

Late in life, Stanislavski shifted emphasis from psyche to deliberate physical tasks: fold a letter, light a cigarette, lace a boot. He found that doing births feeling more reliably than chasing feeling births action. Many confuse this with external “blocking.” In fact, physical actions serve as organic triggers for inner life.

Directors today write a score of actions—a sequence of verb-phrases mapping every beat. Actors memorise not only lines but deeds, freeing the mind to surf emotional waves spontaneously.

Excerpt from a Physical Score

| Beat | Action | Objective Snapshot |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wipe sweat from brow | Hide panic |

| 2 | Strike match—hand trembles | Stall for time |

| 3 | Offer cigarette to partner | Buy favour |

Lab exercise Perform the same score under three imagined circumstances (arctic bunker, Vegas nightclub, pandemic ward). Watch how context reshapes gestures and reveals new emotional colours.

12 Grafting Stanislavski onto Contemporary Techniques

Almost every 20th-century method branches off Stanislavski’s trunk. Knowing origins helps actors mix tools responsibly instead of bouncing between contradictions.

- Meisner Technique: pushes communion to the front via repetition drills.

- Strasberg Method: doubles down on emotion memory for film subtlety.

- Stella Adler: pivots back to imagination and given circumstances.

- Michael Chekhov: codifies psychological gesture—stylised physical actions.

- Practical Aesthetics (Mamet): strips to objective, obstacle, and as-if, minimising “navel-gazing.”

Integration tip Identify why you’re stuck—lack of impulse, thin sensory world, weak objectives—and choose the branch that best solves that specific problem, then return to core principles.

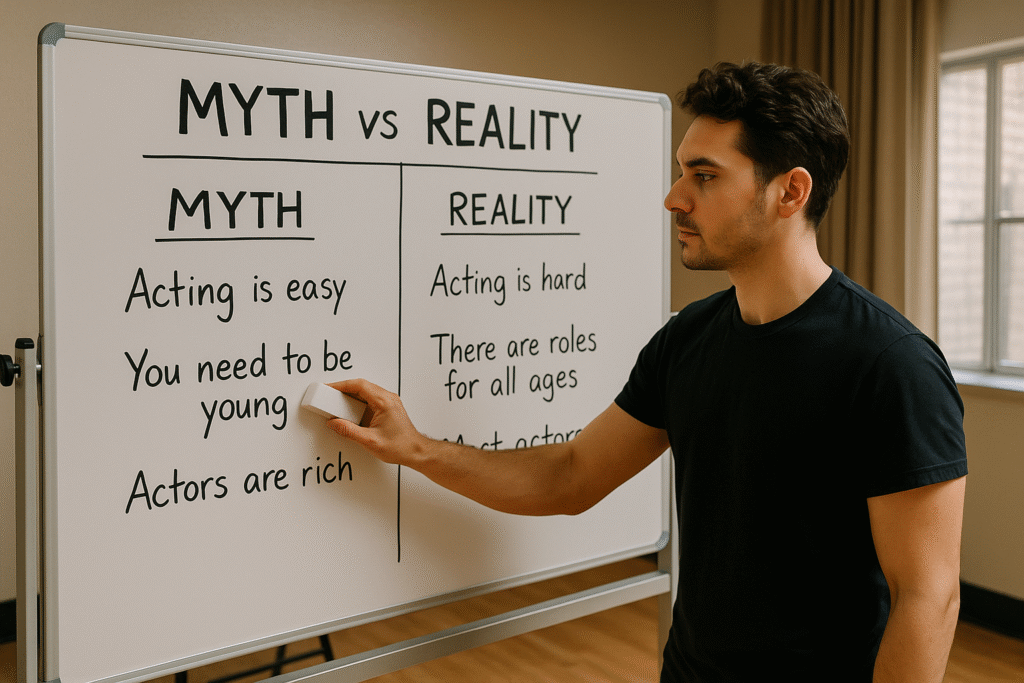

13 Common Pitfalls & Persistent Myths

Lengthy practice breeds folklore. Below is an expanded fact-check table to keep your process clean.

| Myth | Consequence | Reality-Check | Corrective |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Stanislavski = pure emotional recall.” | Actors dig up trauma unsafely. | Emotion memory was one tool; later work stressed actions. | Start with physical score, layer feelings after. |

| “The System is rigid, cerebral, anti-impulse.” | Performances feel dead, over-thought. | The diary shows constant improvisation and play. | Keep journal to notice impulses; never freeze them. |

| “Once you learn the System you never need other methods.” | Creative stagnation. | Stanislavski himself evolved and borrowed. | Treat system as grammar; vary your vocabulary. |

14 Comprehensive Rehearsal Checklist

Use this 10-step cycle before each run-through

- Scan & release tension (Section 2).

- Restate given circumstances aloud (Section 4).

- Announce super-objective in one verb phrase.

- Map beats, objectives, tactics (Sections 6-7).

- Ignite the magic If to freshen stakes (Section 5).

- Practise circles of attention transitions (Section 3).

- Review physical score; run in dumb-show first (Section 11).

- Play with tempo-rhythm variants (Section 9).

- Check communion—non-verbally first, then with text (Section 10).

- Journal findings, flag new obstacles for next session.

Two full passes of this checklist—once slowly, once at performance tempo—compact an entire conservatory curriculum into a repeatable daily warm-up.

15 Why An Actor Prepares Remains Essential Today

Digital tools, motion-capture suits, and AI character-assistants reshape our creative landscape, but the human nervous system has not changed. Audiences still hunger for truthful behaviour under imaginary circumstances. Stanislavski offers a robust framework adaptable to VR, volumetric capture, or immersive AR because it deals with human intention first, technology second.

Furthermore, the book models an ethical approach to craft: respect for partner, audience, and self. “No part of the actor’s body or soul,” writes Stanislavski, “should be coerced.” In an era of deep-fake performances and algorithmic face replacement, that respect for living presence is more revolutionary than ever.

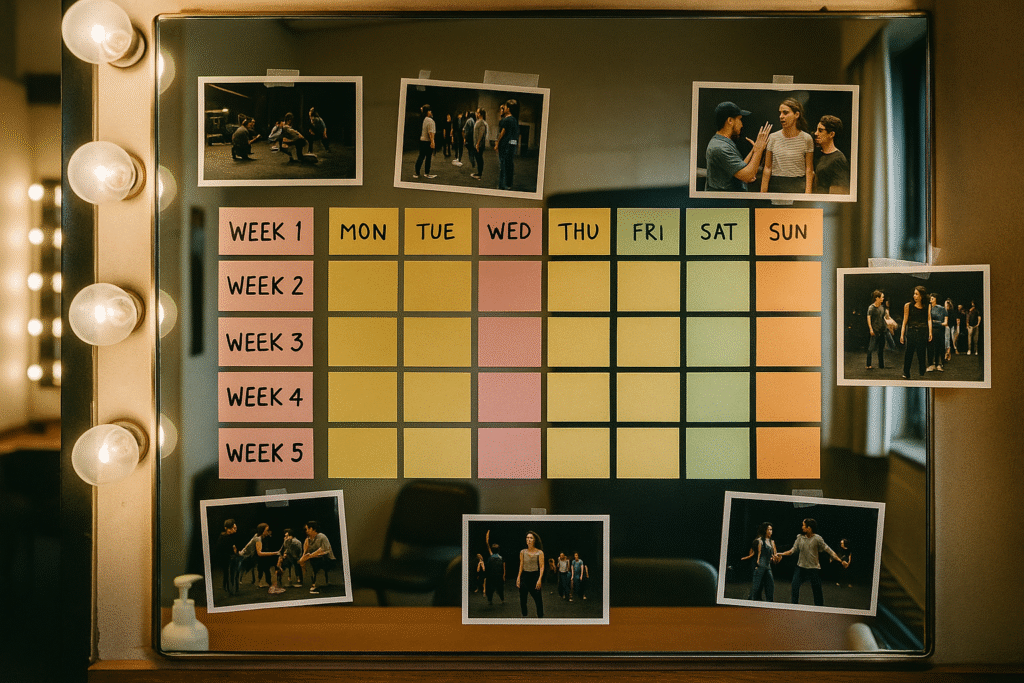

16 Putting It All Together—A Six-Week Self-Study Plan

- Week 1-2 Read An Actor Prepares slowly. Summarise each chapter in your own words, noting exercises that spark curiosity.

- Week 3 Choose a 3-page scene. Apply relaxation, circles of attention, and given circumstances. Record baseline performance.

- Week 4 Layer objectives, obstacles, and physical score. Repeat scene daily, journaling adjustments.

- Week 5 Experiment with emotion memory and tempo-rhythm. Show scene to peers; solicit objective-based feedback.

- Week 6 Integrate partner communion drills and run a public showing, then debrief using the rehearsal checklist.

Milestone metric Compare Week 3 and Week 6 videos side-by-side. Track differences in breath ease, beat clarity, and spontaneous response. Keep footage for your reel.

Conclusion

Stanislavski’s legacy is often reduced to buzzwords—“method acting,” “sense memory,” “being real.”

A careful, patient reading of An Actor Prepares reveals something quieter: a call to disciplined curiosity. The System does not ask actors to bleed for art; it asks them to observe, imagine, and play with scientific rigor and child-like wonder.